In response to the recent

thread on Empire, and because I’m done grading papers, I just want to

rant on say a few words on the term “empire” and why it is historically appropriate to apply the term to modern America. From Merriam-Webster we find the definition:

1 a (1) : a major political unit having a territory of great extent or a number of territories or peoples under a single sovereign authority; especially : one having an emperor as chief of state (2) : the territory of such a political unit b : something resembling a political empire; especially : an extensive territory or enterprise under single domination or control

2 : imperial sovereignty, rule, or dominion While the English usage of empire today often

especially implies rule by an “emperor as chief of state”, as the Merriam-Webster definition relates, historically the usage of the word by historians has had no so limitation. The word empire comes from the Latin root

imperium, which at Rome referred to the supreme administrative power exercised by the kings under the monarchy, then certain magistrates and provincial governors during the Republic, and finally by the principate during what historians refer to as the “Roman Empire.” It this last usage that has particularly colored English usage. But the word

imperium could also refer to dominion in general or the supreme power in any sphere, say that exercised by a military commander or even the head of a household.

The Latin term

imperium was often the preferred word by Romans to translate the Greek word

arche, which, when it refers to a ruling power, is translated into English as empire. So Herodotus talks about the Persian

arche, Thucydides talks about the Athenian

arche and Polybios about the Roman

arche. These last two examples are particularly important, for the Athenians never had an emperor, and at the time Polybios wrote, Rome was still a Republic and had no emperor either. To back up this claim that the term empire is applied to a democratic state without an emperor, and not just some modern liberal conceit, I will only note one famous book on the Athenian

arche, appropriately enough entitled,

The Athenian Empire. Another common synonym for empire in the English language is “hegemony”. This comes from the Greek word

hegemon, meaning general or leader. In history it was first applied to the various Greek city-states, such as Sparta, Athens or Thebes, that sought to extend their influence over other Greek city-states, as in “The Theban hegemony was led by Epaminondas.” Niall Ferguson uses “hegemony” as a synonym for empire in this article

here, where he argues that having a world hegemon (America) isn’t such a bad thing. Another code phrase for a positive view of empire is a play on the Roman Empire’s

Pax Romana -- the so-called “Roman Peace.” So we now often hear of the Pax Americana, most notably in the Project for the New American Century’s famous document of September of 2000,

Rebuilding America’s Defenses. Funny thing about this term is, however, is that Rome never really had a period of peace. And who could forget what Tacitus wrote about those who enjoyed the Roman peace– “They create a desert and call it peace.” I suppose we could say that after WWII the world has enjoyed quite a bit of peace, except for the Cold War. And Korea. And Vietnam. And Grenada. And Panama. And Nicaragua. And the 1st Gulf War. And Afghanistan. And the 2nd Gulf War. But other than those, it’s been pretty peaceful.

All this is a long way of saying that the historic terms for empire (

arche, imperium,

hegemon,

pax Romana...) traditionally have not been limited by historians to just states ruled by emperors. The Persians set up a military-administrative satrapy system to exert control over a wide area of diverse peoples and cultures, the Athenians used their navy to hold together her

arche, Alexander the great used his phalanx, and Rome used her legions during both the Republic and the Principate. The important thing here is not so much whether a king is asserting authority, or a democracy, or a senate, or a principate, what counts is that power or the threat of force is exerted by some military. So to quote Michael Doyle in

Empires"Empire is a relationship, formal or informal, in which one state controls the effective political sovereignty of another political society. It can be achieved by force, by political collaboration, by economic, social, or cultural dependence. Imperialism is simply the process or policy of establishing or maintaining an empire."Of this definition I would only say that under normal circumstances empires need only exert a modicum of overt control. Usually the threat of force and the implicit, often unstated, understanding of the relationship is enough for the weaker partner to act in the interests of the stronger partner as if those interests were their own, because of course the threat of force makes them their own.

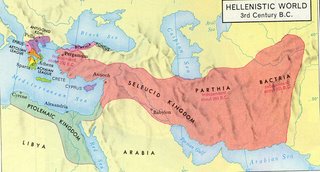

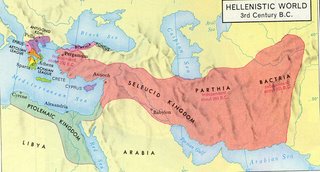

Here are the territories of some Empires throughout history:

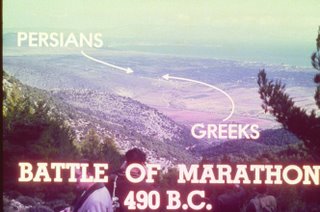

The Persian “Empire” here:

The Athenian “Empire” at it’s height:

Alexander The Great’s “Empire”:

The Empires of Alexander’s Successors:

The Roman Empire at its height:

The Ottomans:

The British:

Now all these maps are a bit misleading if one imagines that all were centrally run from Persepolis, or Athens, or Pella or Rome... In each of these cases, the particular rulers usually did not govern their territories directly. They had surrogates or puppet governments propped up by military bases. Thus, the Romans had a series of military camps along rivers such as the Danube whose very presence kept the locals nearby in line. One of the more common terms for such a situation is “client state”.

Owing to the constraints of technology, all these empires in general required several boots on the ground in the inland places, so that when we hear the word empire today, we tend to imagine Roman soldiers with their plumes in far off places or perhaps British soldiers with their pointed caps. For some reason, we don’t imagine soldiers who wear camouflage in the desert, but never mind that.

Be that as it may, let’s see where American bases are:

Hmm. By any historical criteria, this in and of itself would be called an empire. But of course, it does not reflect the number of nuclear subs lurking under the surface of the ocean or even the ships roving the seas. For some reason some like to call this current world order

neocolonialism, but I have to wonder what they think all those traditional military bases are really doing? I mean, does the US have over 730 military bases around the globe and they’re just window dressing, not really influencing or controlling other country’s policies?

Now, with all this in mind, I’d like to return to the great

stink septic think tank website of William Kristol and his neocon manifesto of 1997, which was signed by many notable current members of the Bush administration:

As the 20th century draws to a close, the United States stands as the world's preeminent power. Having led the West to victory in the Cold War, America faces an opportunity and a challenge: Does the United States have the vision to build upon the achievements of past decades? Does the United States have the resolve to shape a new century favorable to American principles and interests?Or

Our aim is to remind Americans of these lessons and to draw their consequences for today. Here are four consequences:

• we need to increase defense spending significantly if we are to carry out our global

responsibilities today and modernize our armed forces for the future;

• we need to strengthen our ties to democratic allies and to challenge regimes hostile to our interests and values;

• we need to promote the cause of political and economic freedom abroad;

• we need to accept responsibility for America's unique role in preserving and extending an international order friendly to our security, our prosperity, and our principles. The list of signatories here is quite impressive – a who’s who of the Bush administration including Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Salmay Khalilizad, Paul Wolfowitz, Lewis Libby, and Elliot Abrams. In case you missed it, what each of these men signed on to was a policy of spending a ton of money on the military and then using said military to “promote” our interests and “challenge regimes hostile our interests and values.” What exactly do the words “promote” and “challenge” mean in this context other than to put that military to work for the supposed good of our national interest? What does it really mean to put the military to work other than to launch cruise missiles, drop bombs from planes and run tanks over anyone who gets in our way? Perhaps it can also mean that after the bombs drop, you

interfere and stack the deck in the constitution in such a way so that

your interests are protected, all the while hiding it from average people in your own country because it’s really in the interests of a few big companies.

Interestingly enough, in a

roundtable discussion in 1996 on Israel’s economy, and thus 5 years before 9-11, two other denizens of the neoconservative movement and the Bush Administration, Douglas Feith and Richard Perle, famously called for the removal of Saddam Hussein. Is this just a coincidence? William Kristol also called for Saddam’s removal prior to 9-11. Why is that Americans are so ignorant of this? Why is it that only “pseudo” news shows, such as

Colbert’s, are the only ones interviewing these guys and asking them how their Project is going?

One of the chief characteristics of an empire is the belief that the military is the best means to solve one’s international problems. Such a philosophy even has a name. It’s called

militarism. One of the best barometers of whether a county is militaristic is, quite naturally, the priority it gives to military spending. In fact, those who endorse militaristic ideology often scorn other kinds of public expense. Theoretically then, one could measure the militaristic and imperial tendencies of the world’s countries by comparing how much they each spend on their military.

As we can see from this chart, America spends about as much money on her military as the rest of the countries in the world combined. What does that say about our priorities? A wise man once said, “Where your treasure is, there your heart also lies.”

While many militaristic societies in the past have persuaded themselves of the their cause, the world has yet to produce one that was not hated, opposed, and defeated. Sometimes it takes some decades or centuries, but at other times the defeats come stunningly fast. Who would have thought the Soviet Empire would have imploded so quickly? This often happens when a country has a poor leader or a series of poor leaders who open up wars on several fronts thus overstretching the military, or alienating allies by hubristic and self-interested behavior, or relying too much on a military economy, or not really having the resources to pay for all the campaigning and going into debt, or not planning for the inevitable plague or natural disaster. Does any of this sound familiar?